| Micele |

25 april 2016 19:25 |

Citaat:

Oorspronkelijk geplaatst door Wapper

(Bericht 8081444)

Uit uw eigen Wiki link. Veel bruikbaars om mee terug te schieten, ik moest er niet zelf achter gaan zoeken :rofl:

|

Hoe voorspelbaar toch, je zoekt iets totaal onbeduidends in Wiki dat in je kraam past.

Dus je gelooft echt in een samenzwering van die + 60 kinderen die die aliens en UFO getekend hebben. :rofl:

En onder andere deze boeren in Thailand hebben ook een alien gezien en getekend, die zitten ook in het wereldcomplot:

Citaat:

http://www.ufoevidence.org/Cases/Cas...tion=Encounter

Humanoid/Occupant/Encounter Cases

Cases 1 - 16 out of 82 in this section

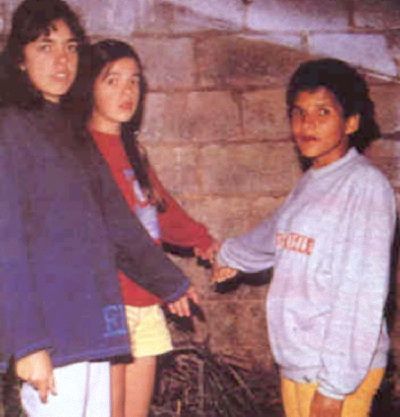

Liliane Fatima Silva, her sister Valquiria and Katia Andrade Xavier - the girls point to the spot where they saw the "terrifying creature".

|

Natuurlijk zullen je daar wel flutkersen vinden die deze landbouwers, kinderen enz... belachelijk willen maken, desinformatie vindt men namelijk ALTIJD, wist je dat niet?

Zet je aluhoedje maar op want mensen van alle slag die aliens en UFO´s gezien en getekend hebben zitten mee in het grote Aliencomplot.

Volgens die link 82 gedocumenteerde Humanoid/Occupant/Encounter-Cases :rofl:

Natuurlijk zijn er wetenschappers die in Aliens geloven, in de eerste plaats John Mack: (als men niet te luit is om te zoeken)

Citaat:

http://johnemackinstitute.org/2004/1...lways-with-us/

A Harvard professor killed in London last week had been vilified for his belief in the ‘third realm’. His theories may not be as mad as some think says Bryan Appleyard

John Mack, professor of psychiatry at Harvard, died after being hit by a car in north London last week. I learnt of the death via an e-mail from the Psychology of the Paranormal Network, an academic group that studies aberrant “anomalistic” phenomena – subjects such as telepathy, ghosts, clairvoyance and alien encounters and abductions.

I was shocked, mainly because I knew the man and liked him, but also because of the banality of his death. Such a bizarre, anguished and exotic life had surely earned a stranger conclusion than an encounter with an alleged drunk in Totteridge.

I met him last year. I had called his office in Boston to arrange a telephone interview, but it turned out he was passing through London and would meet me here. One morning he came round to my flat. He was a very slender, very dark man wearing a flapping raincoat and carrying a large suitcase, both of which seemed to be causing him problems. The permanent expression on his lean, lined face was simultaneously one of distraction and intensity.

He was struck, he said, by the coincidence of my phone call and his visit to London. It seemed significant. We then embarked on a three-hour conversation about the fabric of reality and the way we have deceived ourselves about the true nature of the world. He spoke very slowly and very quietly.

In 1990 Mack had met another acquaintance of mine, Budd Hopkins. Hopkins, a New York artist, had in 1964 seen an unidentified flying object over Cape Cod. He then discovered many people had seen UFOs. In the mid-1970s he also began to come across people who claimed to have encountered and been abducted by aliens.

Using hypnotic regression, he retrieved what appeared to be memories of, among other things, surgery conducted by these aliens on their human victims. Hopkins had become convinced of the reality of these memories and, when he met Mack, he invited him to meet some of the abductees.

Mack met them and also came to believe in their accounts. In 1994 he published a book, Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens. It caused a media firestorm. A Harvard professor had announced that these tales of alien abduction were true. On Oprah Winfrey and Larry King, Mack said it was all true.

The Harvard authorities were appalled. They attempted to get rid of Mack. But on what grounds? The belief that aliens had visited Earth could hardly be grounds for dismissal. If it were, then 5m Americans were wholly unemployable. That is one estimate of the number who might have suffered alien abduction. If all who had encountered aliens or seen UFOs were regarded as unfit for work, then half the nation – including three or possibly four presidents – could not hold down a job.

And so the university pursued a charge of “therapeutic incompetence”. Mack was, after all, a psychiatrist and it could be deemed irresponsible to encourage patients to believe in alien abduction. But Mack had hired a tough lawyer. Gradually he changed the issue into one of academic freedom.

Mack won and held on to his job – though he was to be marginalised by the university. He pursued his own interests via the John E Mack Institute. The website – www.johnemackinstitute.org – describes its goals.

“Our Research, Clinical, and Educational initiatives examine the nature of reality and experience while providing a safe environment for healing discoveries. Our aim is to apply this emerging knowledge to pressing psychological, spiritual and cultural issues.”

Mack continued to write about his meetings with abductees and also to endure bitter criticism and abuse from full time UFO sceptics like the writer Philip J Klass. At one meeting in Seattle in 1994, soon after the publication of his book, Mack was ambushed by both Klass and a woman named Donna Bassett. Bassett had been one of his abductee patients but, she told the meeting, she had lied.

“I faked it,” she said. “Women have been doing it for centuries.”

Mack, she claimed, just told abductees what they wanted to hear. Klass, who was in the audience, waded into the row, accusing Mack of making “false innuendoes”. He had said that the Bassett incident had been fixed by Klass.

“I’m not convinced one way or the other,” he said, “whether she did in fact hoax or whether she has in fact had these experiences herself. I don’t know.”

Mack went on to become the foremost villain of the sceptics and the saint of the believers. Through him flowed the multiple crises of modernity and secularity. Is this all there is? Is what we are being told about the nature of the world true? Or have we lost some deep, ancient wisdom that now only surfaces as aberrant and ridiculed phenomena such as alien abduction?

“Other cultures have always known that there were other realities,” he told the Seattle conference, “other beings, other dimensions. There is a world of other dimensions, of other realities that can cross over into our world.”

Long before aliens came into his life, Mack had always believed something like this. He had first made his name with a Pulitzer prize-winning biography of TE Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia – but his primary work was at the Harvard Medical School. He was always a dissident. He campaigned against the arms race in the Seventies and was a leading figure in International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War which collectively won the Nobel peace prize in 1985. He also conducted a series of interviews with people involved in nuclear decision- making, including President Jimmy Carter, which led him to conclude that it was “a whole boys’ club . . . You couldn’t question what you were doing, that would be emasculating”.

But the direction of his psychiatric work was much more controversial. He became involved with EST – Erhard Seminars Training – which he described to me as “a technology for blowing your mind, basically”. He also took up Stanislav Grof’s holotropic breathwork that uses rapid breathing to enter an altered state of consciousness.

“I travelled into past lives, emotions and events. I realised the psyche could travel. It was not limited to the brain and the body. Spirituality, rather than being an embarrassing high-mindedness, which is what it is in secular culture, became very tangible.”

He was obsessed with the idea that the contemporary scientific account of the world was simply wrong. Alien abduction came as yet further evidence.

Why, he wondered, do we not believe the tales of abductees? In other cultures – and in our own in the past – people routinely accepted encounters with spirits. The default human belief condition is that there is another world in close proximity to ours and the two routinely interact. We are the weirdos in denying what everybody else takes to be a self-evident truth.

But Mack’s belief in abductions was subtly and importantly different from that of people like Budd Hopkins. Hopkins is a “nuts and bolts” believer. He thinks the aliens are as solid as you and me and they intend to take over the world. Mack, in contrast, became a “third realmer”.

The first realm is that of the mind, the second that of the world, but there is a third realm to which modernity denies us access. And it is there that the aliens live. Sony used to advertise its PlayStation computer game console by saying it was “the third place”, a direct reference to this idea, which implied that playing computer games created a new reality outside the mind and outside the world.

What exactly this means is hard to imagine, rather like trying to picture a four-dimensional cube. But it is clear what it implies: that modern man wears blinkers, he has been denied – or he denies himself – access to the true nature of the world. The scientific imagination has concealed from us the teeming reality of the third realm.

Of course, it would be easy to dismiss all this, to say that Mack was crazy and his followers gullible. Nobody has provided any physical evidence of the abduction phenomenon. All we have is thousands of accounts, many of them retrieved, dubiously, under hypnosis. I have been hypnotised myself and I saw a flying saucer, a vision that seemed like a memory. But I am sure I have never seen any such thing. Hypnotism generates new visions more persuasively than it retrieves old ones.

To say that, however, is to say very little. Whether these things are “true” or “real” is, in fact, a trivial matter. The important issue is the fact that they are seen, felt, endured, suffered and celebrated by millions. This points to deep truths about the way we apprehend the world. John Mack was troubled by something that troubles us all – maybe not aliens, exactly, but a discontinuity, an absence, a lack.

After our talk I took him to Paddington station. He struggled still with his raincoat and his case. He was a man who did not fit in the world and now he has left it. I shall miss his strange, troubled presence.

A science and philosophy columnist for the Sunday Times of London, Bryan Appleyard is looked upon by many as one of today’s most outspoken and articulate critics of science.

© 2004 Bryan Appleyard

Originally published in The London Times

Sunday, October 03, 2004

|

|